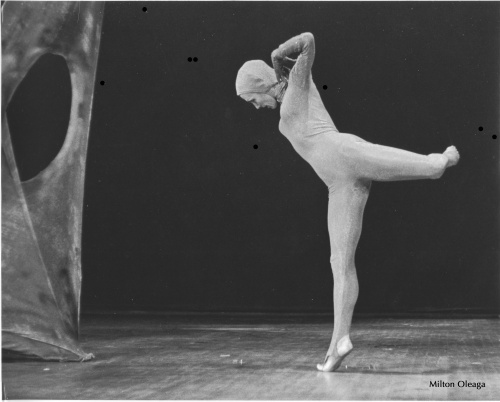

Milton Oleaga’s Eye on José Limón

Milton Oleaga (b. Aug. 3, 1929; d. July 30, 2013), from what he told me, was born in Germany of parents of Spanish Basque origin. He told me of Hitler’s Youth marching in the streets when he was a child, with their infamous salute of “Heil, Hitler!” He told me how naturally as a young boy in such conditions, these special Youth seemed to be to what he should aspire.

Then came the move to Sheepshead Bay, Long Island with his late older brother (lived and died in New Orleans) and his mother and his Merchant Marine father. Then came shock and confusion that nobody in the states was heil-hitlering, and whoa, there was another story he didn’t know about.

I can’t claim to be Milton’s biographer. I’m just sharing what he’s told me over 43 years. I’ve saved 120 90-minute tapes of his cassette letters overs 4 decades. Each letter is a treasure trove, as his mind meandered from one story to another as he recorded in solitude . . . probably to many other friends too.

Relevant especially to the respectful-as-I-can-manage-it presentations of Milton’s widely diverse Oeuvre (in the most pretentious sense, and, ironically his True Eye) . . . are the hours of photo-by-photo verbal commentaries now on CDs waiting for me to learn to do a slideshow of each book synced with his voice (Help?). Milton meanders just as literarily (he must have owned and read 7000 books) over a single person’s face (he calls them his “Beauty Shots”) . . . and that sends him on a tangent to another story and another and . . . it’s just entrancing.

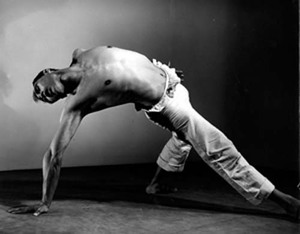

I must have done something good in a past life to have encountered this man, and to be so honored as he trusted me to care for the work he had not already dispersed to friends and Luigi (lifelong) and beautiful dancers in Luigi’s classes, and (illegal! what a bad man for capturing beauty!) sneaking his camera into major New York dance company performances. He LOVED NYCB, Martha Graham, Juilliard performances, Harkness Ballet, José Limón Dance Company, and on and on . . . not to mention his vast collection of “Fish Books”, also with CD commentary: for many years, Milton loved to get back to Sheepshead Bay (from his 20s westside NYC apt.) to head out on day-fishing boats . . . a whole other pocket of culture ongoing as I write. AND, if he couldn’t get any more prolific . . . there are thousands of NYC 60s and 70s “subversive” street shots; Milton would carry his camera, ready to shoot, then pretend to look away as the subject approached . . . spontaneous cultural gems of a time long since past.

This first post I hope will be received by the José Limón Foundation for their archives. Because I never studied directly with him, I stole Wikipedia’s extensive writing on his life and work (incredible that he was a Latino Veteran in World War II . . . Milton too was a Veteran of the Army, where he first stumbled into and taught himself photography).

Yet, I share his legacy by way of Josephine and Hermene Schwartz, founders of The Dayton Ballet (which produced Rebecca Wright, Donna Wood, Joseph and Daniel Duell, Stuart Sebastian, Amy Danis, Vickie Garlitz and others . . . me too. Miss Jo and Miss Hermene had studied with Doris Humphrey whose exploration of fall and rebound movement was so much at the core of Master Limón’s technique.

Also, many years later when I had a studio, I was fortunate to learn from Gail Chodera (a graduate of the Univ. of Tucson’s Dance Dept.?) who taught Limón’s technique.

If anyone reading this sees any person they can identify, or any work, or costume person, or . . . letting me know via the comments would be kindly requested . . . every dancer deserves to be named for their aspirations towards beauty. And know that if you find yourself here, I would be happy to ship the original photos to you for your care (please pay shipping) and pleasure. That is what Milton wanted.

note: many of the Harkness Ballet photographs that Milton took appear in the very early posts on http://HarknessBallet.wordpress.com, a blog that has been seen by 25,000 people in over 20 countries. Please like each of these blogs to receive my trickle of postings automatically.

Stolen from Wikipedia

Born January 12, 1908

Culiacán, Mexico

Died December 2, 1972 (aged 64)

Years active1929–1969

José Arcadio Limón (January 12, 1908 – December 2, 1972 [at age 64]) was a pioneer in the field of modern dance and choreography. In 1928, at age 20, he moved to New York City where he studied under Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman. In 1946, Limón founded the José Limón Dance Company. His most famous work is called The Moor’s Pavane (1949), based on Shakespeare‘s Othello.[1]

Contents

Early career

José Arcadio Limón was born January 12, 1909 in Culiacán, Mexico, the eldest of twelve children. In 1915, his family moved to Los Angeles, California. After graduating from Lincoln High School, Limón attended UCLA as an art major. He moved to New York City in 1928 to study at the New York School of Design. In 1929, he was inspired to dance after attending one of Harald Kreutzberg and Yvonne Georgi’s performances.[2]

Limón enrolled in the Humphrey-Weidman school later that year and, just a year later, performed on Broadway. Later in 1930, Limón choreographed his last dance, “Etude in D Minor”, a duet with Letitia Ide. In addition to his duet partner, Limón recruited schoolmates Eleanor King and Ernestine Stodelle to form “The Little Group”. From 1932 to 1933, Limón made two more broadway appearances in the musical revue Americana and Irving Berlin‘s As Thousands Cheer, choreographed by Charles Weidman. Limón also tried his hand at choreography this year at Broadway’s New Amsterdam Theatre. Limón made several more appearances throughout the next few years in shows such as Humphrey’s New Dance, Theatre Piece, With my Red Fires, and Weidman’s Quest. In 1937, he was selected as one of the first Bennington Fellows. At the Bennington Festival at Mill College in 1939, Limón created his first major choreographic work, titled Danzas Mexicanas. After five years, however, Limón would return to Broadway to star as a featured dancer in Keep Off the Grass under the choreographer George Balanchine.

In 1941, Limón left the Humphrey-Weidman company to work with May O’Donnell. They co-choreographed several pieces together, such as “War Lyrics” and “Curtain Riser”. During this time, Limón met Pauline Lawrence, who he would later marry on October 3, 1942. The partnership with O’Donnell dissolved the following year, and Limón created for a program at Humphrey-Weidman.

In 1943, Limón made his final appearance on Broadway with Balanchine’s Rosalinda, a piece he performed with Mary Ellen Moylan. He spent the rest of that year creating dances on American and folk themes at the Studio Theatre before being drafted into the Army in April 1943. During this time, he collaborated with composers Frank Loesser and Alex North, choreographing several works for the U.S. Army Special Services. The most well-known among these is Concerto Grosso.

Limón Dance Company

Upon attaining American citizenship in 1946, Limón formed the Limón Dance Company. When Limón began his company, he asked Humphrey to be the artistic director, making it the first modern dance company to have an artistic director who was not also the founder. The company had its formal debut at Bennington College, playing such pieces as Doris Humphrey’s Lament and The Story of Mankind. Among the first members were Pauline Koner, Lucas Hoving, Betty Jones, Ruth Currier, and Limón himself. Dancer and choreographer Louis Falco also danced with the José Limón Dance Company from 1960–70, and Falco starred opposite to Rudolph Nureyev in Limon’s Moor’s Pavane on Broadway from 1974-75. While working with Humphrey, Limón developed his repertory with Doris Humphrey and established the principles of the style that were to become the Limón technique. By 1947, the company had reached New York, debuting at the Belasco Theatre with Humphrey’s Day on Earth. In 1948, the company first appeared at the Connecticut College American Dance Festival and would remain in residence each summer for many years. After choreographing The Moor’s Pavane, it received the Dance Magazine Award for the year’s most outstanding choreography. In the spring of 1950, Limón and his group appeared in Paris with Ruth Page, becoming the first American modern dance company to appear in Europe.

In 1951, Limón joined the faculty of The Juilliard School where a new dance division had been developed. He also accepted an invitation to Mexico City’s Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, where he created six works. Between 1953 and 1956, he choreographed a number of shows and created roles in Humphrey’s Ruins and Visions and Ritmo Jondo. In 1954, the Limón Company was one of the first to take advantage the U.S. State Department’s International Exchange Program with a company tour to South America. The company later embarked on a five-month tour of Europe and the Near East and, again, to South America and Central America. It was during this time that Limón received his second Dance Magazine Award.

In 1958, Doris Humphrey, who had been the artistic director for the Limón Company, died and Limón took over her position. Between 1958 and 1960, Limón choreographed with Pauline Koner. During this time, he received an honorary doctorate from Wesleyan University. In 1962, the company returned to Central Park as the opening performance to New York’s Shakespeare Festival. The next year, under sponsorship of the U.S. State Department, he toured the Far East for twelve weeks, choreographing The Deamon to a score by Paul Hindemith, who conducted the première.

In 1964, he went on to receive the Capezio award and was appointed the artistic director of the American Dance Theatre at Lincoln Center. The following year, Limón appeared in an NET special titled The Dance Theater of José Limón. A few years later, he established the José Limón Dance Foundation as a not-for-profit corporation and received an honorary doctorate from the University of North Carolina. In 1966, after performing with the company at the Washington Cathedral, Limón received a government grant of $23,000 from the National Endowment for the Arts. The next year, Limón choreographed Psalm, earning him an honorary doctorate from Colby College. He and his company were also invited to perform at the White House for President Lyndon B. Johnson and King Hassan II of Morocco. Limón’s final appearances onstage as a dancer were in 1969, when he performed in The Traitor and The Moor’s Pavane at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. He created two more pieces during this time, and received an honorary doctorate from Oberlin College.

Later Years

In 1970, Limón was diagnosed with prostate cancer. In the last years of his life, despite being stricken with cancer, he choreographed and filmed a solo dance interpretation for CBS. In 1971, Limón lost his wife, to cancer and, in December 1972, at the age of 64, José Limón also died from cancer.[3]

Legacy

During the course of his career, Limón created what is now known as the “Limón technique” according to the Limón Institute, the technique “emphasizes the natural rhythms of fall and recovery and the interplay between weight and weightlessness to provide dancers with an organic approach to movement that easily adapts to a range of choreographic styles.”[4]

Although there have not been any dancers from the Limón company who have founded prominent companies of their own, his style can still be seen in performances today. Dance companies such as the Doug Varone and Dancers company continue to teach Limón’s style of dancing. The company itself is still active, with the express purpose of maintaining the Limón technique and repertory.[5]

In 1973, the José Limón Collection was given to the New York Public Library Dance Collection by Charles Tomlinson. Eleven years later, a book, entitled “The Illustrated Dance Technique of José Limón” was published, explicitly describing José Limón’s technique. In 1997, he was inducted into the National Museum of Dance’s Mr. & Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney Hall of Fame.

Technique

José Limón was a great admirer of Doris Humphrey and his technique reflects clearly the teaching of Humphrey. Like Doris, his main goal was to express his personal relationship with the outside world through his movements in an organic manner. His technique was deeply influenced by Doris’ ideas, for example, the “quality of body’s weight”[6] which was represented with the fall and rebound. Also he was influenced by her “vocabulary of suspension and succession”[6]. His technique is not codified, because he believed that a structured technique would limit creativity which was vital for his technique. His technique helped his students to find their own movement and personal uniqueness. He was interested in the expression through movement and not in beauty of movements. He used to say to his students “when you stop trying to be pretty . . . you will be beautiful”.[7] He emphasized the exploration of movement in its natural form and in the expression of pure humanity. He motivated his students to always “strive for simplicity and clarity without extraneous movement, superfluous energy or unwanted tension that would interfere with the original intent.”[8] His dance represented a pure expression of emotion and passion, it was energetic, and it traveled and interacted through space. He considered that the body was an instrument of communication and expression that could “speak”. He mentioned “The modern idiom has extended a range of expressive movement and communicative gesture tremendously. The modern dancer strives for a complete use of body as his instrument”.[6] “He used isolated parts of the body to ‘speak’ with individual qualities and referred to this idea as ‘voices of the body’.”[6] For example, he used the movement of the shoulder in different directions that initiated simultaneously the movement of the arms, torso, or legs. For him this represented a dialect, where the movement of one part of the body could have “a voice with a motivation behind it”[6] Also he considered the body as an orchestra, where one part of the body could represent one instrument and other part of the body could represent a different instrument independently. For him, there were multiple combinations of movement between the different parts of the body. For him the use of the arms were very important, they followed curved shapes and interacted with space through the effort shapes. Also he considered that breathing was indispensable because it allowed movement to flow continuously and to start from the center of the body. In his technique, he paid great attention to the movements of the chest. He considered that the chest was a powerful part of the body that could portray emotion. He experimented different movements of the chest to explore different emotional possibilities.Most of the time, he used contraction with the torso and he emphasized “inward and outward rotations of the knee.”[8]

Choreography

When Limon danced he showed his true feelings, a great passion, intensity, and mainly spontaneity. “Limon’s choreography embodies the impulse and drive of his dancing, but it is clear that the Apollonian mind was there informing his thought and giving shape to his creation. He had great skill in developing and varying movement from a supreme economy of thematic material. His works based on theme and variation are so harmoniously conceived that it is hard to imagine any gesture, motion or choreographic element not being essential to the whole.”[7] He was a genius choreographer who understood and played with the music perfectly. He combined his phrases with counterpoint “adding dimension to the music”.[7] Not all the choreographers were able to combine so gratefully music with dance during the 20th century like him.

Dionysian and Apollonian

In his dance and in his classes he motivated the existence of the Dionysian [Dionysis?] and Apollonian [Apollo?]. Most of the time his dance was inclined mostly by the Dionysian but mainly his intention was to work with both. The combination of the opposite characters made his dance so interesting. José Limón mentioned: “My dance, therefore, would have only two characters, a protagonist and an antagonist, eternally opposed and irreconcilable. They would represent the conflict between authority and the rebel, orthodoxy and the heretic, order and chaos.”[9]

Choreography

| Year | Title |

|---|---|

| 1930 | Etude in D Minor |

| 1930 | Bacchanale |

| 1930 | Two Preldes |

| 1931 | Petite Suite |

| 1931 | B Minor Suite |

| 1931 | Mazurca |

| 1932 | Bach Suite |

| 1933 | Canción y Danza |

| 1933 | Danza (Prokofiev) |

| 1933 | Pièces Froides |

| 1933 | Roberta |

| 1935 | Three Studies |

| 1935 | Nostalgic Fragments |

| 1935 | Prelude |

| 1936 | Satiric Lament |

| 1936 | Hymn |

| 1937 | Danza de la Muerte |

| 1937 | Opus for Three an Props |

| 1939 | Danzas Mexicanas |

| 1940 | War Lyrics |

| 1941 | Curtain Raiser |

| 1941 | This Story Is Legend |

| 1941 | Three Inventories on Casey Jones |

| 1941 | Three Women |

| 1941 | Praeludium: Theme and Variations |

| 1942 | Chaconne |

| 1942 | Alley Tune |

| 1942 | Mazurca |

| 1943 | Western Folk Suite |

| 1943 | Fun for the Birds |

| 1944 | Deliver the gods. |

| 1944 | Hi, Yank |

| 1944 | Interlude Dances |

| 1944 | Mexilinda |

| 1944 | Rosenkavalier Waltz |

| 1945 | Concert Grasso |

| 1945 | Eden Tree |

| 1945 | Danza (Arcadio) |

| 1946 | Masquerade |

| 1947 | La Malinche |

| 1947 | The Song of Songs |

| 1947 | Sonata Opus 4 |

| 1949 | The Moor’s Pavane |

| 1950 | The Exiles |

| 1950 | Concert |

| 1951 | Los Cuatros Soles |

| 1951 | Dialogues |

| 1951 | Antigona |

| 1951 | Tonantizintla |

| 1951 | The Queen’s Epicedium |

| 1951 | Redes |

| 1952 | The Visitation |

| 1952 | El Grito (Revised version of Redes) |

| 1953 | Don Juan Fantasia |

| 1954 | Ode to the Dance |

| 1954 | The Traitor |

| 1955 | Scherzo (Barracuda, Lincoln, Venable) |

| 1955 | Scherzo (Johnson) |

| 1955 | Symphony for Strings |

| 1956 | There Is a Time |

| 1956 | A King’s Heart |

| 1956 | The Emperor Jones |

| 1956 | Rhythmic study |

| 1957 | Blue Roses |

| 1958 | Missa Brevis |

| 1958 | Serenata |

| 1958 | Dances |

| 1959 | Tenebrae 1914 |

| 1959 | The Apostate |

| 1960 | Barren Sceptre |

| 1961 | Performance |

| 1961 | The Moirai |

| 1961 | Sonata for Two Cellos |

| 1962 | I, Odysseus |

| 1963 | The Demon |

| 1963 | concerto in D Minor After Vivaldi |

| 1964 | Two Essays for Large Ensemble |

| 1964 | A Choreographic Offering |

| 1965 | Variations on a Theme of Paganini |

| 1965 | My Son, My Enemy |

| 1966 | The Winged |

| 1967 | Mac Aber’s Dance |

| 1967 | Psalm |

| 1968 | Comedy |

| 1968 | Legend |

| 1969 | La Piñata |

| 1970 | The Unsung (as a work in progress) |

| 1971 | Revel |

| 1971 | The Unsung |

| 1971 | Dances for Isadora |

| 1971 | And David Wept |

| 1972 | Orfeo |

| 1972 | Carlota |

| 1986 | Luther |

References[edit]

- Pollack & Humphrey Woodford 1993, p. 31.

- Limón 1998, p. 16.

- Dunbar 2003, p. 135.

- “Limón Institute”. José Limón Dance Foundation. 2011-01-30. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- “Heritage: Jose Limón”. José Limón Dance Foundation. 2003-04-29. Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- Dunbar 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Dunbar 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Dunbar 2003, p. 39.

- Cohen 1966, p. 27.

Citations

- Cohen, Selma Jeanne (1966). The Modern Dance; Seven Statements of Belief. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6003-2.

- Dunbar, June (2003). José Limón: The Artist Re-viewed. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-90-5755-121-5.

- Limón, José (1998). Garafola, Lynn, ed. José Limón: an Unfinished memoir. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.ISBN 978-0-8195-6505-1.

- Pollack, Barbara; Humphrey Woodford, Charles (1993). Dance is a Moment: a Portrait of José Limón in Words and Pictures. Princeton Book Company. ISBN 978-0-87127-183-9.

Further reading

- Reich, Susanna (2005). Born to Dance: The Story of José Limón. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-689-86576-n Dance Foundation website